Violence in Dieppe

Tony Mayne

Contents Page

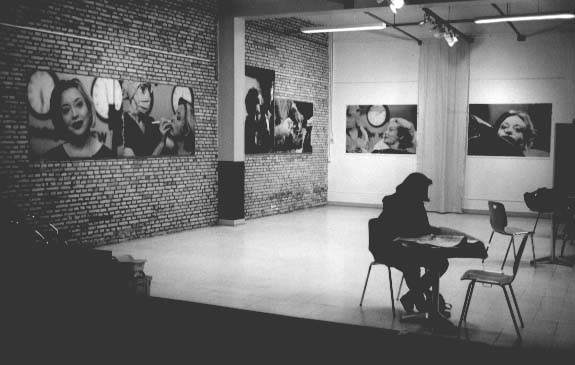

© Carol Hudson, in the show at les Tourelles

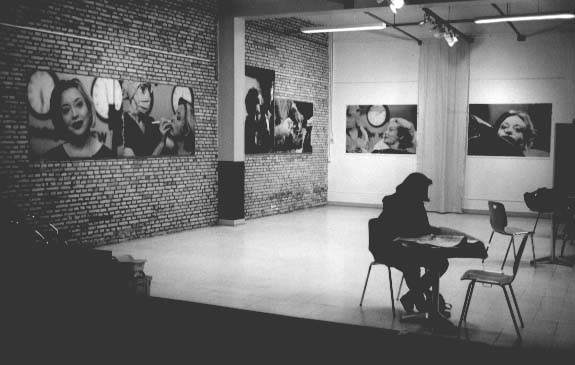

© Carol Hudson, in the show at les Tourelles

Dieppe's 11th annual Mois de l'Image (March 23rd - April 19th), illustrated by over thirty photographers at eight different locations, used 'Violence' as its theme. The interpretations varied from strong social documentary approaches (photojournalism in Algeria and the Balkans) to more reflective pieces (Photoshop and empty factories).

German photographer, Thomas Dworzak, visited Azerbaijan and Tchetchenia over a four year period, covering the secessionist war against the USSR. Some of his work did cover burials and exhumed bodies, but a lot of it dwelt on the people in the street. It was the influence of the war on the culture that was his primary observation in this exhibition. The heavy black frames (reminiscent of condolence cards), in which these black and white images were presented, added emphasis to the feeling of 'life going on' for the survivors of this tragedy.

The strongest depictions of violence in a war zone were taken in Algeria by members of the New Press and SIPA agencies. The Algerian civil war/ revolution has gone largely unreported in Britain. The images at Dieppe Service Communication were powerful and moving, but left me feeling like an intruder into the personal trauma of the participants. They included grieving widows, the bodies of tortured children being reclaimed from the sewers into which they had been dumped, messages on the wall written in the blood of victims, refugees, and mass graves (all supported by statistics about the numbers of people killed in each village running into tens and hundreds). Looking at these images on gallery walls somehow seemed to sanitise the horrors depicted: I felt like someone who has just watched a public execution. I spoke to a photographer and an agency executive and they were as aware of these problems as of the dangers in the field.

If Dworzak's pictures in the Town Hall, taken of 'ordinary life', could be captioned 'Life goes on', the Algerian pictures could only be captioned 'Death goes on'.

At the Ecole Nationale de Musique, Eric Prinvault also showed disorder in people's lives. In this case no war had taken place, but the people were surplus to, and unwanted by, society - the poor, the asylum seekers, the Other. One memorable picture - an African woman and her baby sitting in a room/ detention centre, surrounded by glass windows insulating her from the street life immediately outside - was a perfect metaphor for

alienation.

The closed factories in Marie-Ellen and Nick Broshenka's 'Histoires d'Usines' consisted of large monochrome interiors of abandoned factories, many works featuring hand colouring, tinting or selective toning. Wooden easels and frames (together with the packing boxes in which the work arrived at the Centre Jean Renoir used as part of the display) added to the feeling of stilled utility. This was, for me, some of the best work on view in Dieppe - static, thoughtful, majestic and balanced: not portraying direct violence, arguably illustrating 'after the violence'. As Media Students <'Burgin's Babes'> might say, 'This work was about Closure'.

The most personally upsetting work on display ( the only one that sent me outside for the proverbial 'breath of fresh air') was that of Orlan. Extending her oeuvre as as a performance artist, Orlan makes the body of her work the work on her body. The work on display at the Maison de Jeunes et de la Culture consisted of photographs of her early performances and some of her seven surgical operations. The centrepiece was a video installation of her most recent [and most disturbing] operation, when she had the kind of prosthetic bumps common in cosmetic surgery inserted under the skin of her face, plus what resemble nascent 'horns' at the temples. Her final appearance is further from conventional ideas of 'beauty' (both in the common and artistic senses) than her appearance before she embarked on her remarkable medical Odyssey. The theoretical justification for remodelling herself is perfectly consistent with current Art hypotheses, although few theoreticians would subject themselves to such drastic unetherised operations. This strange mixture of aesthetics and anaesthetics poses many interesting questions - such as 'Who is the Artist?', 'What is the work of Art?' and 'Who is the director of operations?'. The answer to these questions, and many more, could be 'Orlan'.

View of Orlan exhibition

Another offering which altered the subject's faces (but less painfully) was Aziz and Cucher's 'Dystopia' - portraits with the eyes, nostrils and mouths removed by Photoshop techniques. Their initial impact was quite dramatic - seeing a face which became unreadable because the very areas that our attention singles out for closer inspection prove to be information-free zones. This was the only body of work where the artists were committing the violence - why remove eyes rather than warts, and mouths rather than wrinkles? Subsequent viewing (from Jenny Matthews' Women in Conflict' exhibition) of the picture of Phong - a Vietnamese girl born without eyes as a result of America's Agent Orange 'gift' - whose face resembles Aziz and Cucher's work, has clouded my original appraisal.

View of Installion

A set of very large X-ray pieces, depicting two life-size people simulating combat and, finally, kissing and making up, was a particularly interesting piece of work. Each piece was constructed of up to 25 separate X-ray plates. Paris-based Xavier Lucchesi told me that he had attached the plates to a wall, posed his models, and then given an exposure to each tableau. For exhibition each set of transparencies were clipped together and the backgrounds were painted translucent red. The pieces worked as a set, and some details (such as a gun or a camera in someone's hand) provided fascinating X-rays - the hardness of the metal emphasising the vulnerability of the body. The Town Hall, with glass walls on either side, provided an excellent gallery for these huge transparencies.

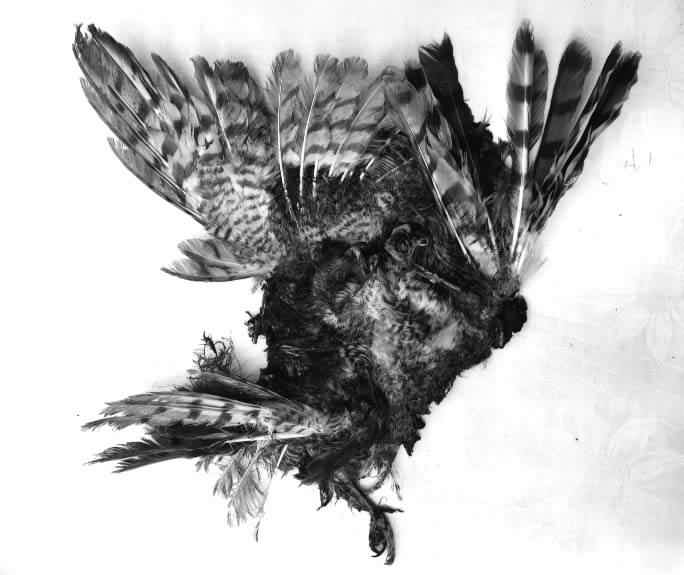

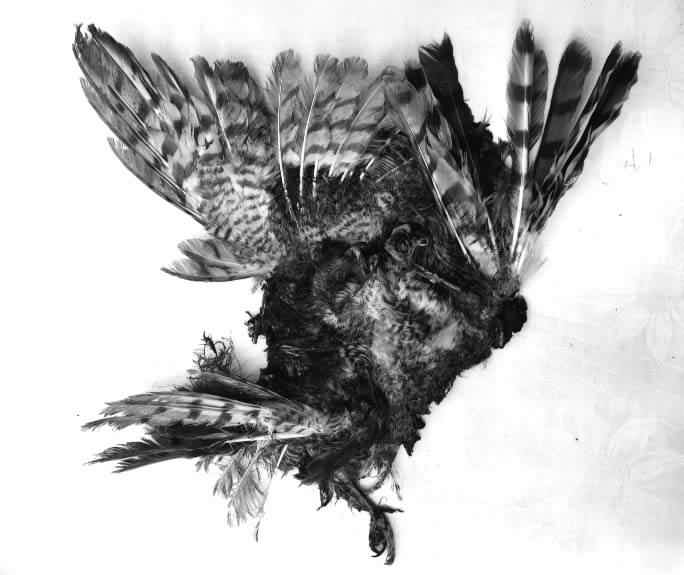

The final venue, Les Tourelles, contained mixed work by twenty local and foreign photographers. The work varied from smashed motor cars to a boy using a toy gun as a brain-corrosive artifact to threaten his sister. Included this year were some of (LIP member) Carol Hudson's Stilled Lives pictures of birds which suffered violent deaths.

There is a Mois de l'Image every year from mid-March to mid-April, so if you missed this year's, do put it in your diary for 1999. A day return on the Lynx from Newhaven is quite cheap and you could see most of the exhibitions in a day.

Contents Page

© Carol Hudson, in the show at les Tourelles

© Carol Hudson, in the show at les Tourelles